A conceptual architecture for Digital Nudges to assist in crisis communication around COVID-19

The first two articles in our “Dealing with Disruption” series looked at how digital technologies might enable governments around the world to nudge citizens towards cooperation and coordinated action in containing COVID-19, and to address issues of hand washing, face touching, self-isolation, collective action, and crisis communication. In this article, the SAP Institute for Digital Government (SIDG) will present a conceptual architecture for Digital Nudges and demonstrate how it could be applied to improve crisis communications relating to a second-wave outbreak of the Coronavirus.

Using digital nudges to support government responses to coronavirus

To demonstrate how our conceptual architecture might be applied, we will consider the scenario of a second-wave outbreak of the Coronavirus, such as was recently experienced in Australia.

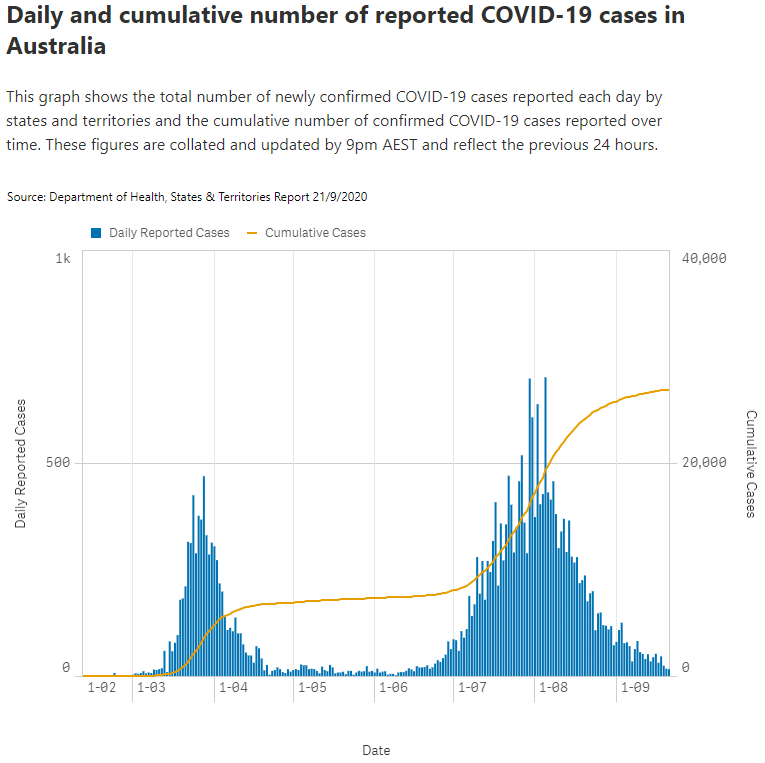

Figure 1: The first- and second-wave outbreaks of COVID-19 in Australia.

Australia’s first case of COVID-19 was identified on 25 January 2020. The number of new cases rapidly increased and peaked nine weeks later, with 469 new cases reported on 28 March. The Australian government responded very successfully with a 3-step framework for flattening the curve, and by mid-April there were a relatively low number of new cases being reported daily. Although the virus had not been eliminated, it appeared to have been suppressed sufficiently for lockdown restrictions to be eased across Australia. Unfortunately, 25 new cases were identified in Melbourne on 20 June, foreshadowing a second-wave and prompting a reinforcement of restrictions to contain the outbreak. Even so, Australia’s second-wave proved more difficult to contain than the first, peaking at 725 new cases reported on 5 August.

Due to the localized nature of the second-wave outbreak, stay-at-home restrictions were reintroduced only in metropolitan Melbourne and Mitchell shire. Most notably, nine public housing towers in North Melbourne and Flemington were immediately locked-down, with residents of 33 Alfred Street subsequently required to isolate for two weeks. While it was generally agreed that this was a necessary measure, the immediacy of the action combined with various communication challenges resulted in widespread confusion and concern among the 3,000 public housing tenants. These comments captured the sentiment at the time:

- “When I came back home I did see hundreds of cops everywhere, so it was really intimidating.”

- “It’s been getting more and more intense, people are really panicking.”

- “We weren’t told any information, they just shut us down, didn’t let us leave our houses.”

- “I just feel like we’re being treated like criminals.”

- “We do not need 500 officers guarding the nine towers. We need nurses, we need counsellors, we need interpreters.”

In what has been an unprecedented year, the hard lockdown of Melbourne’s public housing towers was an unprecedented action by the Australian government, law enforcement and public health services. To that point, Australian citizens had not experienced a lockdown under guard, except in cases of returned citizens undertaking hotel quarantine.

In special cases such as this, efficient and effective crisis communication is key – not only in ensuring compliance – but in promoting cooperation through credibility, empathy and respect. Behavioral Science can assist by influencing individual decisions towards the most positive outcome, and digital technologies can be used to scale and personalize traditional nudges to improve outcomes for mass cohorts.

Conceptual Architecture for digital nudges

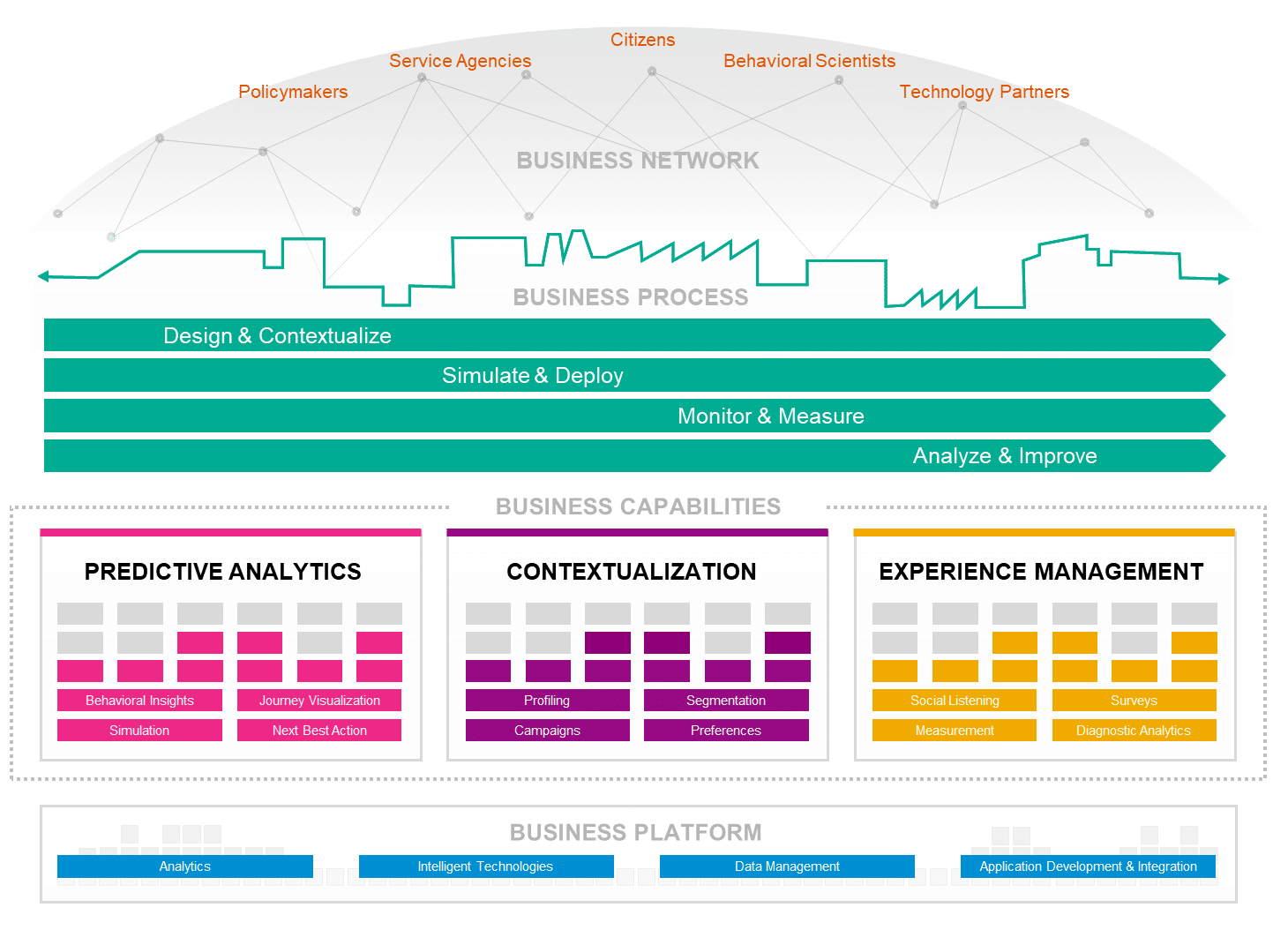

Figure 2: A conceptual architecture for digital nudges.

Nudging is a delicate process, with significant preparation required to avoid unintended consequences – especially when the stakes are as high as they are in the case of COVID-19. These stakes are raised even higher when the nudges are to be delivered by governments, at scale, using digital technologies. The leading practice is to optimize utility and mitigate risk using an iterative process of randomized controlled trials with rapid cycle evaluation. Whether the nudge is to be delivered as part of a trial, or to the population at large, an iteration of the nudging process typically spans:

- Design and contextualize: The nudge is designed to achieve the outcome of interest, based on an exploration of the available data. A key consideration is the situational and social context of the environment in which the nudge is to be deployed. In the case of crisis communications, nudges need to be credible and actionable, but also show respect and express empathy for citizens’ circumstances.

- Simulate and deploy: Randomized controlled trials can be used to simulate the likely response to a given nudge. A variation of this approach would involve using digital twins, to enable simulations to be run faster and safer than with human subjects. In the case of crisis communications, these simulations could be aligned to the accepted thresholds of a national or local containment strategy.

- Monitor and measure: Having deployed the nudge, social listening and IoT devices can be employed to monitor the actual response. Although it may be difficult to measure the effectiveness of nudges as a behavioral modifier, a control group who does not receive the nudge may be used. In the case of crisis communications, we might also consider performance against “fake news” as a measure of effectiveness.

- Analyze and improve: Here we distinguish between measurement and analysis, specifically within the context of diagnostics – analyzing why a particular action has been taken or a particular outcome achieved. Based on this analysis, improvements can be made to the design of the nudge, and thus the iteration continues. In the case of crisis communications, certain visualizations (e.g. infographics) might be published to encourage community cooperation and coordinated action.

Digital nudges: Core capabilities

As described in our first article, predictive analytics, contextualization, and experience management are the core capabilities required to deliver digital nudges. Breaking down these capabilities will enable us to illustrate how they can support policymakers and service agencies, working with behavioral scientists and technology partners, to improve the effectiveness of traditional nudges.

- Predictive Analytics:

- Behavioral Insights: The ability to detect patterns in citizen behavior, based on transactional and experiential data. For example, based on their prior responses to government requests, we can expect Citizen X to comply with stay-at-home orders.

- Journey Visualization: The ability to visualize the citizen’s journey over time, including major life events, changes in circumstance, and their interactions with government. For example, based on the healthcare, social services and financial supports they have recently accessed, Citizen X is likely a vulnerable person who will need additional supports.

- Simulation: The ability to simulate the likely responses to a digital nudge, including the ability to compare alternative approaches. For example, Nudge A will increase compliance with stay-at-home orders by 5%, with 80% confidence.

- Next Best Action: The ability to recommend the optimal course of action, based on (autonomous) machine learning. For example, Nudge A will be most effective for Citizen X, while Nudge B will be most effective for Citizen Y.

- Contextualization:

- Profiling: The ability to assemble a digital profile of a citizen, by combining data from multiple sources (as permitted by government regulations). For example, we know that Citizen X is at high risk, since they are over 80 years of age and live in high-density public housing.

- Segmentation: The ability to create target groups, comprising citizens with similar profiles and needs. For example, Segment A comprises citizens of working age, who are likely concerned about the impact of stay-at-home orders on jobs.

- Campaigns: The ability to proactively outreach to target groups with nudges tailored to their circumstances. For example, Nudge A will be delivered to citizens of working age, while Nudge B will be delivered to citizens over the age of 65.

- Preferences: The ability to communicate with citizens via their preferred channel, and at their preferred time and place. For example, Citizen X usually responds promptly to SMS sent around lunchtime.

- Experience Management:

- Social Listening: The ability to monitor social media to track changes in citizen sentiment over time. For example, citizens under lockdown are complaining that police presence is making them feel like criminals.

- Surveys: The ability to solicit direct feedback from citizens. For example, Citizen X responded that they couldn’t understand the specifics of the stay-at-home order because English is their second language and no translation service was provided.

- Measurement: The ability to measure the response to a digital nudge, based on transactional and experiential data. For example, Nudge A increased compliance with stay-at-home orders by 3%, compared with the control group who did not receive the nudge.

- Diagnostic Analytics: The ability to uncover why certain nudges are, or aren’t, working. For example, Nudge A was widely criticized as being disrespectful, resulting in a lower level of compliance than anticipated.

The underlying business platform supports the design, development, and management of our digital nudges.

- Analytics: The ability to analyze transactional and experiential data. Desirable features include the ability to:

- surface actionable insights based on predictions;

- dynamically drill-down into records of interest;

- visualize citizen journeys over time; and

- update data and visualizations in real-time.

- Intelligent Technologies: The ability to build, execute and manage machine learning applications. Desirable features include the ability to:

- process big data holdings to build advanced machine learning models;

- support profiling and segmentation of data in line with contextualization capabilities;

- generate predictions and next best action recommendations; and

- make improvements based on (autonomous) machine learning.

- Data Management: The ability to access and work with big data, in real-time. Desirable features include the ability to:

- consolidate data from multiple sources;

- work with transactional data in real-time, without impacting operational systems;

- work with analytical data in-place, without the need for replication; and

- ensure the security and privacy of citizen data.

- Application Development & Integration: The ability to develop and integrate business applications. Desirable features include the ability to:

- accelerate the design and development of advanced machine learning applications;

- run simulations in support of what-if analysis;

- support an open ecosystem of development partners; and

- integrate with external systems (e.g. geographic information systems).

In presenting this conceptual architecture, our intent has been to provide a framework that governments can use to deliver digital nudges. We believe this framework to be general-purpose, while acknowledging that certain scenarios will require additional capabilities. Our chosen use case of crisis communications serves as an illustrative example. Please note that, since this conceptual architecture is vendor-agnostic, the described capabilities could be sourced from any technology provider.

To read more about how digital technology can be used to improve public sector services, visit SAP Australia’s Public Sector homepage.